Child/Adolescent Services

A core part of Milestone's vision is to provide high quality mental health services to the children, adolescents, and parents within our community. Milestone is committed to working within these populations to help younger clients achieve academically, relationally, and spiritually. In order to achieve this vision the majority of Milestone's therapists are extensively trained and experienced in working with younger populations and their caregivers. In to meet the unique needs of these clients Milestone utilizes play therapy as its' primary treatment modality. Within the perameters of play therapy we also utilize sand tray therapy, music therapy, art therapy, behavioral modification, cognitive-behavioral therapy, filial therapy, and animal therapy.

What is Play Therapy?

In recent years a growing number of noted mental health professionals have observed that play is as important to human happiness and well being as love and work (Schaefer, 1993). Some of the greatest thinkers of all time, including Aristotle and Plato, have reflected on why play is so fundamental in our lives. The following are some of the many benefits of play that have been described by play theorists.

Play is a fun, enjoyable activity that elevates our spirits and brightens our outlook on life. It expands self-expression, self-knowledge, self-actualization and self-efficacy. Play relieves feelings of stress and boredom, connects us to people in a positive way, stimulates creative thinking and exploration, regulates our emotions, and boosts our ego (Landreth, 2002). In addition, play allows us to practice skills and roles needed for survival. Learning and development are best fostered through play (Russ, 2004).

Why Play in Therapy?

Play therapy is a structured, theoretically based approach to therapy that builds on the normal communicative and learning processes of children (Carmichael, 2006; Landreth, 2002; O'Connor & Schaefer, 1983). The curative powers inherent in play are used in many ways. Therapists strategically utilize play therapy to help children express what is troubling them when they do not have the verbal language to express their thoughts and feelings (Gil, 1991). In play therapy, toys are like the child's words and play is the child's language (Landreth, 2002). Through play, therapists may help children learn more adaptive behaviors when there are emotional or social skills deficits (Pedro-Carroll & Reddy, 2005). The positive relationship that develops between therapist and child during play therapy sessions provides a corrective emotional experience necessary for healing (Moustakas, 1997). Play therapy may also be used to promote cognitive development and provide insight about and resolution of inner conflicts or dysfunctional thinking in the child (O'Connor & Schaefer, 1983; Reddy, Files-Hall & Schaefer, 2005).

What Is Play Therapy?

... toys are a child's words!

Initially developed in the turn of the 20th century, today play therapy refers to a large number of treatment methods, all applying the therapeutic benefits of play. Play therapy differs from regular play in that the therapist helps children to address and resolve their own problems. Play therapy builds on the natural way that children learn about themselves and their relationships in the world around them (Axline, 1947; Carmichael, 2006; Landreth, 2002). Through play therapy, children learn to communicate with others, express feelings, modify behavior, develop problem-solving skills, and learn a variety of ways of relating to others. Play provides a safe psychological distance from their problems and allows expression of thoughts and feelings appropriate to their development.

Play therapy simply defined is "the systematic use of a theoretical model to establish an interpersonal process wherein trained play therapists use the therapeutic powers of play to help clients prevent or resolve psychosocial difficulties and achieve optimal growth and development."

How Does Play Therapy Work?

Children are referred for play therapy to resolve their problems (Carmichael; 2006; Schaefer, 1993). Often, children have used up their own problem solving tools, and they misbehave, may act out at home, with friends, and at school (Landreth, 2002). Play therapy allows trained mental health practitioners who specialize in play therapy, to assess and understand children's play. Further, play therapy is utilized to help children cope with difficult emotions and find solutions to problems (Moustakas, 1997; Reddy, Files-Hall & Schaefer, 2005). By confronting problems in the clinical Play Therapy setting, children find healthier solutions. Play therapy allows children to change the way they think about, feel toward, and resolve their concerns (Kaugars & Russ, 2001). Even the most troubling problems can be confronted in play therapy and lasting resolutions can be discovered, rehearsed, mastered and adapted into lifelong strategies (Russ, 2004).

Who Benefits from Play Therapy?

Although everyone benefits, play therapy is especially appropriate for children ages 3 through 12 years old (Carmichael, 2006; Gil, 1991; Landreth; 2002; Schaefer, 1993). Teenagers and adults have also benefited from play techniques and recreational processes. To that end, use of play therapy with adults within mental health, agency, and other healthcare contexts is increasing (Pedro-Carroll & Reddy, 2005; Schaefer, 2003). In recent years, play therapy interventions have also been applied to infants and toddlers.

How Will Play Therapy Benefit A Child?

Play therapy is implemented as a treatment of choice in mental health, school, agency, developmental, hospital, residential, and recreational settings, with clients of all ages (Carmichael, 2006; Reddy, Files-Hall & Schaefer, 2005).

Play therapy treatment plans have been utilized as the primary intervention or as an adjunctive therapy for multiple mental health conditions and concerns (Gil & Drewes, 2004; Landreth, Sweeney, Ray, Homeyer & Glover, 2005), e.g. anger management, grief and loss, divorce and family dissolution, and crisis and trauma, and for modification of behavioral disorders (Landreth, 2002), e.g. anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity (ADHD), autism or pervasive developmental, academic and social developmental, physical and learning disabilities, and conduct disorders (Bratton, Ray & Rhine, 2005).

Research supports the effectiveness of play therapy with children experiencing a wide variety of social, emotional, behavioral, and learning problems, including: children whose problems are related to life stressors, such as divorce, death, relocation, hospitalization, chronic illness, assimilate stressful experiences, physical and sexual abuse, domestic violence, and natural disasters (Reddy, Files-Hall & Schaefer, 2005). Play therapy helps children:

- Become more responsible for behaviors and develop more successful strategies.

- Develop new and creative solutions to problems.

- Develop respect and acceptance of self and others.

- Learn to experience and express emotion.

- Cultivate empathy and respect for thoughts and feelings of others.

- Learn new social skills and relational skills with family.

- Develop self-efficacy and thus a better assuredness about their abilities.

How Long Does Play Therapy Take?

Each play therapy session varies in length but usually last about 30 to 50 minutes. Sessions are usually held weekly. Research suggests that it takes an average of 20 play therapy sessions to resolve the problems of the typical child referred for treatment. Of course, some children may improve much faster while more serious or ongoing problems may take longer to resolve (Landreth, 2002; Carmichael, 2006).

How May My Family Be Involved in Play Therapy?

Families play an important role in children's healing processes. The interaction between children's problems and their families is always complex. Sometimes children develop problems as a way of signaling that there is something wrong in the family. Other times the entire family becomes distressed because the child's problems are so disruptive. In all cases, children and families heal faster when they work together.

The play therapist will make some decisions about how and when to involve some or all members of the family in the play therapy. At a minimum, the therapist will want to communicate regularly with the child's caretakers to develop a plan for resolving problems as they are identified and to monitor the progress of the treatment. Other options might include involving a) the parents or caretakers directly in the treatment in what is called filial play therapy and b) the whole family in family play therapy (Guerney, 2000). Whatever the level the family members choose to be involved, they are an essential part of the child's healing (Carey & Schaefer, 1994; Gil & Drewes, 2004).

Who Practices Play Therapy?

The practice of play therapy requires extensive specialized education, training, and experience. A play therapist is a licensed (or certified) mental health professional who has earned a Master's or Doctorate degree in a mental health field with considerable general clinical experience and supervision.

With advanced, specialized training, experience, and supervision, mental health professionals may also earn the Registered Play Therapist (RPT) or Registered Play Therapist-Supervisor (RPT-S) credentials¹ conferred by the Association for Play Therapy (APT).

Authors

This information was initially crafted by JP Lilly, LCSW, RPT-S, Kevin O'Connor, PhD, RPT-S, and Teri Krull, LCSW, RPT-S and later revised in part by Charles Schaefer, PhD, RPT-S, Garry Landreth, EdD, LPC, RPT-S, and Dale-Elizabeth Pehrsson, EdD, LPC, RPT-S. Linked mental health conditions and concerns and behavioral disorders were drafted by Pehrsson and Karla Carmichael, PhD, LPC, RPT-S respectively. Research citations were compiled by Pehrsson and Oregon State University graduate assistant Mary Aguilera.

What is Sand Tray Therapy?

Sandtray therapy is a dynamic and expressive form of psychotherapy that allows clients to express their inner worlds through symbol and metaphor. Humanistic sandtray therapy emphasizes a deep and accepting therapeutic relationship and an approach to sandtray processing that focuses on here-and-now experiencing. We believe that as people grow and develop in childhood and adolescence, they all lose touch with who they are. They may have been taught that certain feelings are acceptable while others are not. In this process of denying who they truly are, they become disconnected from their true selves. Humanistic sandtray therapy provides an experience of reconnecting to one’s true self, of rediscovering dreams, hopes and visions.

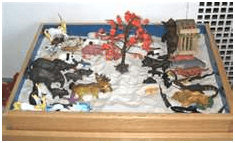

Like play therapy with young children, sandtray therapy provides an experience that is active, nonverbal, indirect, and symbolic. However, with clients who are 15 and older and do not have the developmental limitations of preoperational and concrete operational children, humanistic sandtray therapy capitalizes on the verbal and abstract thinking abilities of this age and extends the impact of the scene creation phase of sandtray to theprocessing phase of sandtray. The scene creation phase, in which clients arrange their miniatures in the tray, is very important and is central to the sandtray therapy experience. In humanistic sandtray therapy, the processing phase provides an additional experience that builds upon the scene creation phase and revolves around it. Throughout the processing phase of sandtray, clients look at their scene and experience the impact of it.

Sandplay has an accelerating history. It goes back to an early decade of this century when H.G. Wells wrote about his observing his two sons playing on the floor with miniature figures and his realizing that they were working out their problems with each other and with other members of the family. Twenty years later Margaret Lowenfeld, child psychiatrist in London, was looking for a method to help children express the "inexpressible." She recalled reading about Wells' experience with his two sons and so she added miniatures to the shelves of the play room of her clinic. The first child to see them took them to the sandbox in the room and started to play with them in the sand. And thus it was a child who "invented" what Lowenfeld came to identify as the World Technique (Lowenfeld, 1979).

When Dora Kalff, Jungian Analyst in Zurich, heard about the work in England, she went to London to study with Lowenfeld. She soon recognized that the technique not only allowed for the expression of the fears and angers of children, but also encouraged and provided for the processes of transcendence and individuation she had been studying with C.G. Jung. As she developed the method further, she gave it the name "sandplay" (Kalff, 1980). Jungian analysts from five countries joined Kalff in founding the International Society for Sandplay Therapy in 1985. The American affiliate society, Sandplay Therapists of America, was founded in 1988. The first issue of the Journal of Sandplay Therapy appeared in 1991.

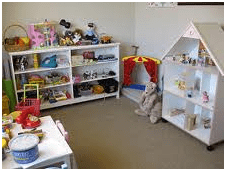

The essentials of sandplay therapy are a specially proportioned sandtray, a source of water, shelves of miniatures of multitude variety: people, animals, buildings, bridges, vehicles, furniture, food, plants, rocks, shells-the list goes on-and an empathic therapist who provides the freedom and the protection that encourages children (or adults) to experience their inner, often unrealized, selves in a safe and non-judgmental space. The therapist as a witness is an essential part of the method, but this therapist is in the mode of "appreciating", not "judging", what the sandplayer does. It is necessary that the therapist follows the play and stays in tune with it, but not intrude. The therapist follows the child.

Given an empathic therapist, children rarely need any encouragement to start making pictures or scenes and playing in the sand. They come to it naturally. They may engage the therapist in the play but unlike some therapies there is no attempt on the part of the therapist to interpret to the child what the therapist may understand of what is going on in the sandplay. The process of touching the sand, adding water, making the scenes, changing the scenes, seems to elicit the twin urges of healing and transformation which are goals of therapy. This does not mean that the therapist remains distant or unresponsive. But the emphasis is on following the child rather than on imposing a structure on the play or even guiding the play. The child's psyche becomes the guide rather than the therapist.

The child may need to engage the therapist in the play. I recall a little ten-year old girl whom I call Kathy who came to therapy with problems of fears of failure and of her anger that had built up over the years. She was fearful of expressing her anger and typically placed fences in the tray after having expressed anger toward or about any member of the family. We did not have to talk about this. By placing the fences around jungle animals, she was able to experience an ability to do something about controlling these animals and, in extension, about her anger and then to feel safer to sense and express her own aggressive feelings. At first this did not include me, but eventually she translated her sandplay into an interaction with me. She came to a point where she alternated between having us "fight" with toy cannons in the sand tray and playing out positive feelings towards me. But there was no need to interpret the transference. Kathy worked it out herself. She had us build a sand castle together in the final tray (Bradway and McCoard, 1997).

The tray provided for Kathy, as it does for other children, the place to work through many phases of self-healing and growing up. For example, a child's placing water and food for animals in the tray is often a step in learning how to obtain nourishment on their own rather than having to depend on its being offered by others and thus provides a step towards a higher level of ego autonomy. Sources of energy other than food, such as wells, gasoline pumps, windmills, often appear during periods of transition when the ego needs an additional supply of energy in order to cope with a struggle between inner and outer forces. And most significantly, the tray provides for the experiencing of wholeness.

This information is adapted from articles written by Stephen A. Armstrong & Kay Bradway, Ph.D., JA

D5 Creation

D5 Creation